Archives municipales de Brest :

Plan du port et ville de Brest par Jacques-Nicolas Bellin, 1764, (cote : 5Fi1125).

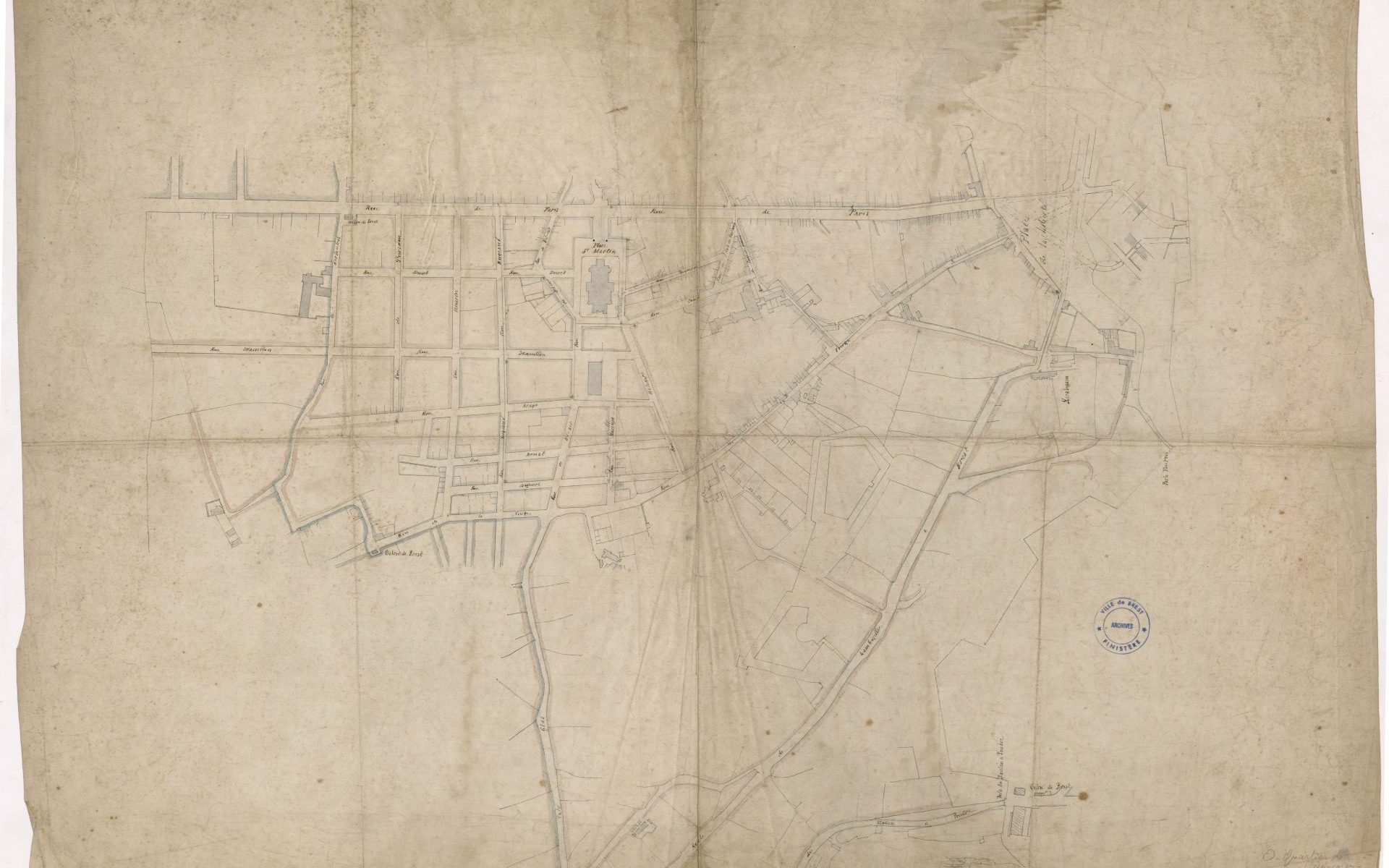

Plan de Brest et de ses environs, relatif aux projets pour l’agrandissement de l’enceinte, 1790 par Jean-Nicolas Desandrouins ingénieur, directeur à Brest des places de Bretagne (cote : 5Fi1113).

Joseph-Victor Tritschler, Projet non réalisé du pont à Brest (Penfeld), 19e siècle, 1843 (cote : 2 Fi 00409).

Pont tournant de Brest à Recouvrance, 1880 (cote : 2005.5.4).

L’Arsenal de Brest, sans date (cote : 12Fi2110).

Carte postale : vue sur l’arsenal, les bâtiments, des navires, la grande grue, la porte Tourville, le bassin à droite la rue Louis Pasteur, le centre ville de Brest, en arrière plan le clocher de l’église Saint Louis (cote : 12Fi2109).

Carte postale : Rue de Siam avant-guerre (cote : 3Fi019-018).

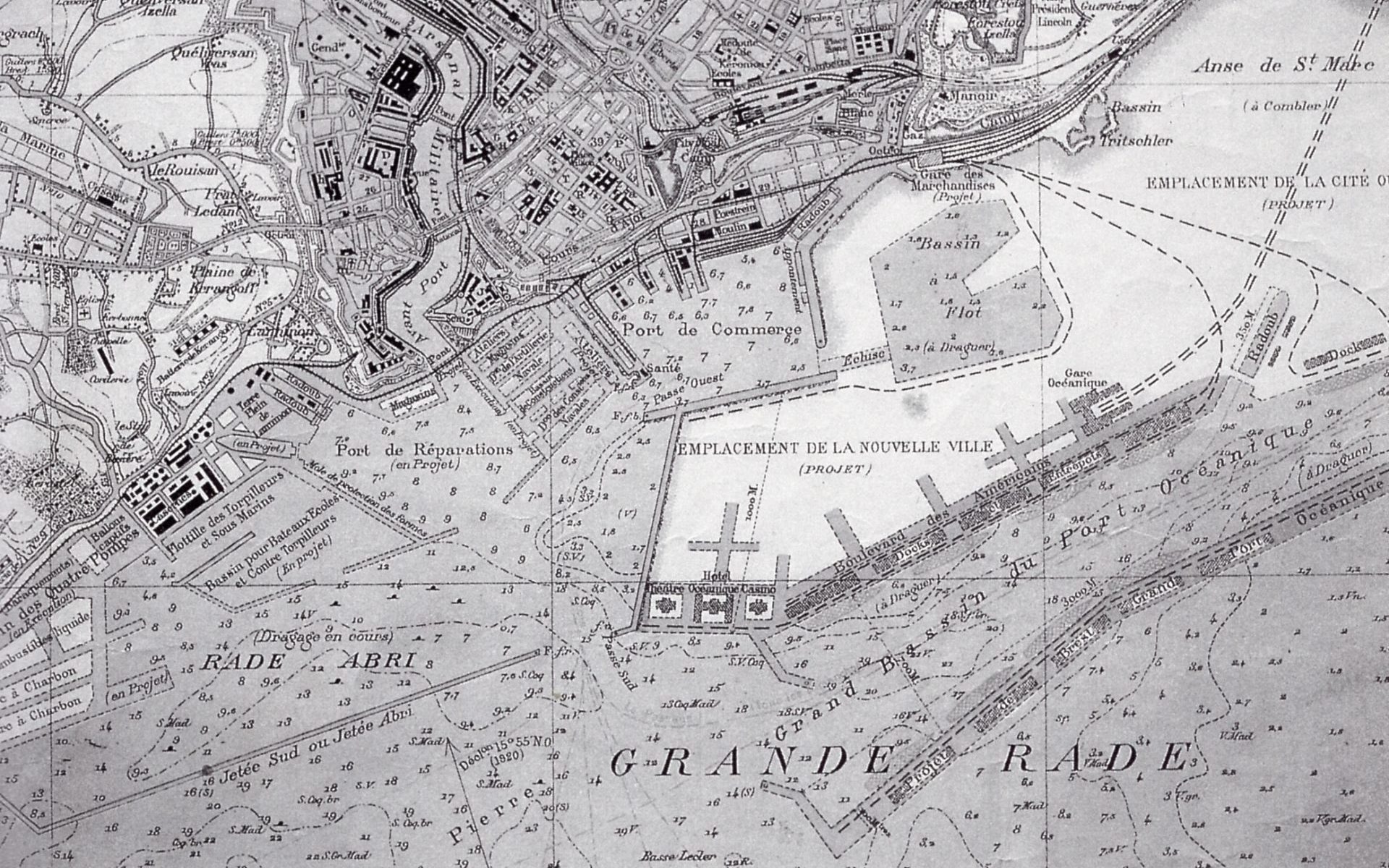

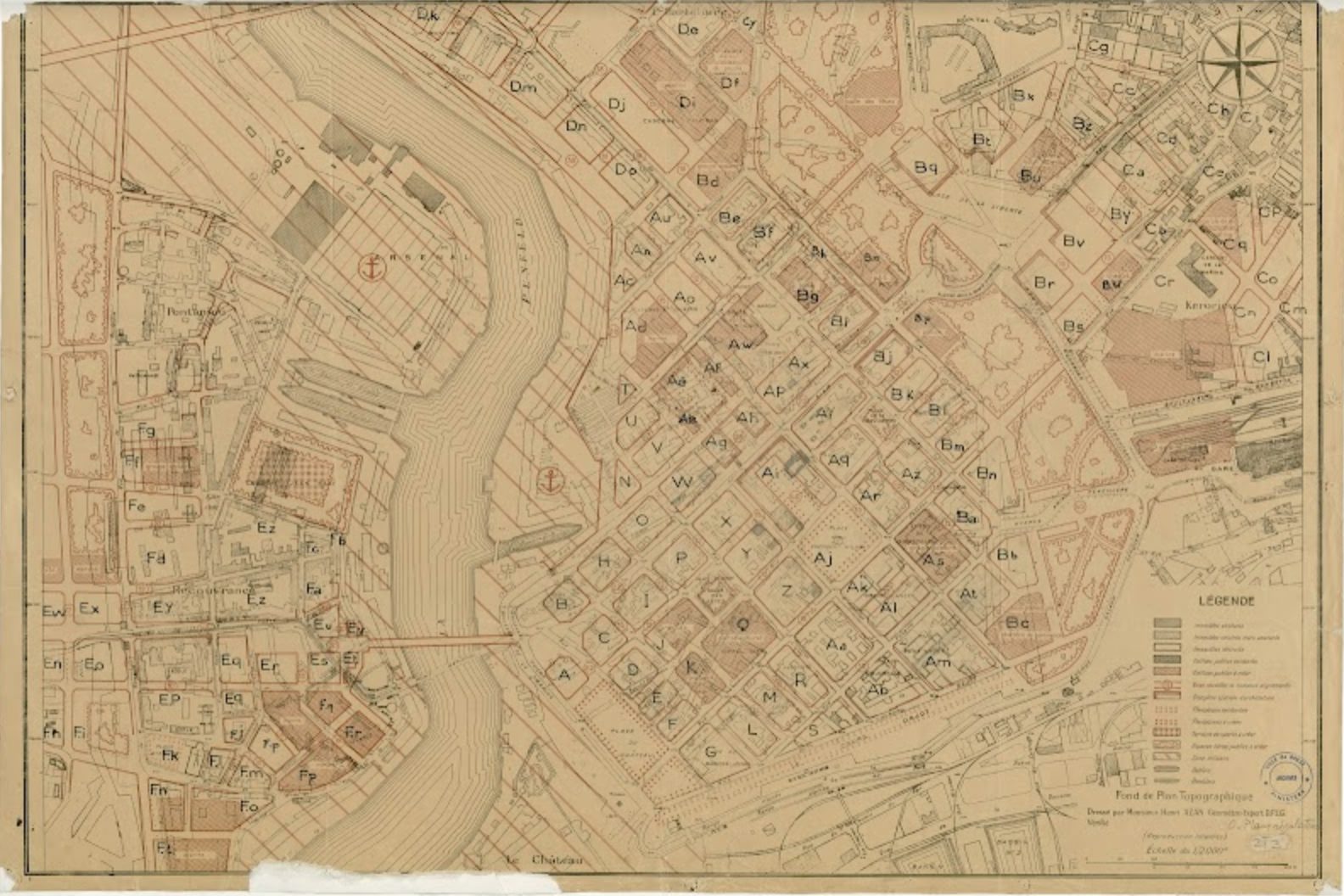

Georges Milineau, Plan d’aménagement, d’embellissement et d’extension de la ville de Brest, 1920 (cote : 5Fi760 ou 5Fi761).

Planimètre de la ville de Brest, 1937 (cote : 5Fi838).

Le Pont national ou Grand Pont, Destruction : vue du tablier plongeant dans la Penfeld, en arrière-plan les ruines à Recouvrance, 1945 (cote : 2Fi05175).

Jean-Baptiste Mathon, Plan de reconstruction et d’aménagement, 1948 (cote : 5Fi881).

Plan de Brest, 1956 (cote : 5Fi897).

Rue de Siam, années 1950 (cote : 3Fi019-094).

Bijouterie Gouriou immeuble mer 33 Rue de Siam à Brest, (07/1950), Façade : élévation (cote : 5Fi2081).

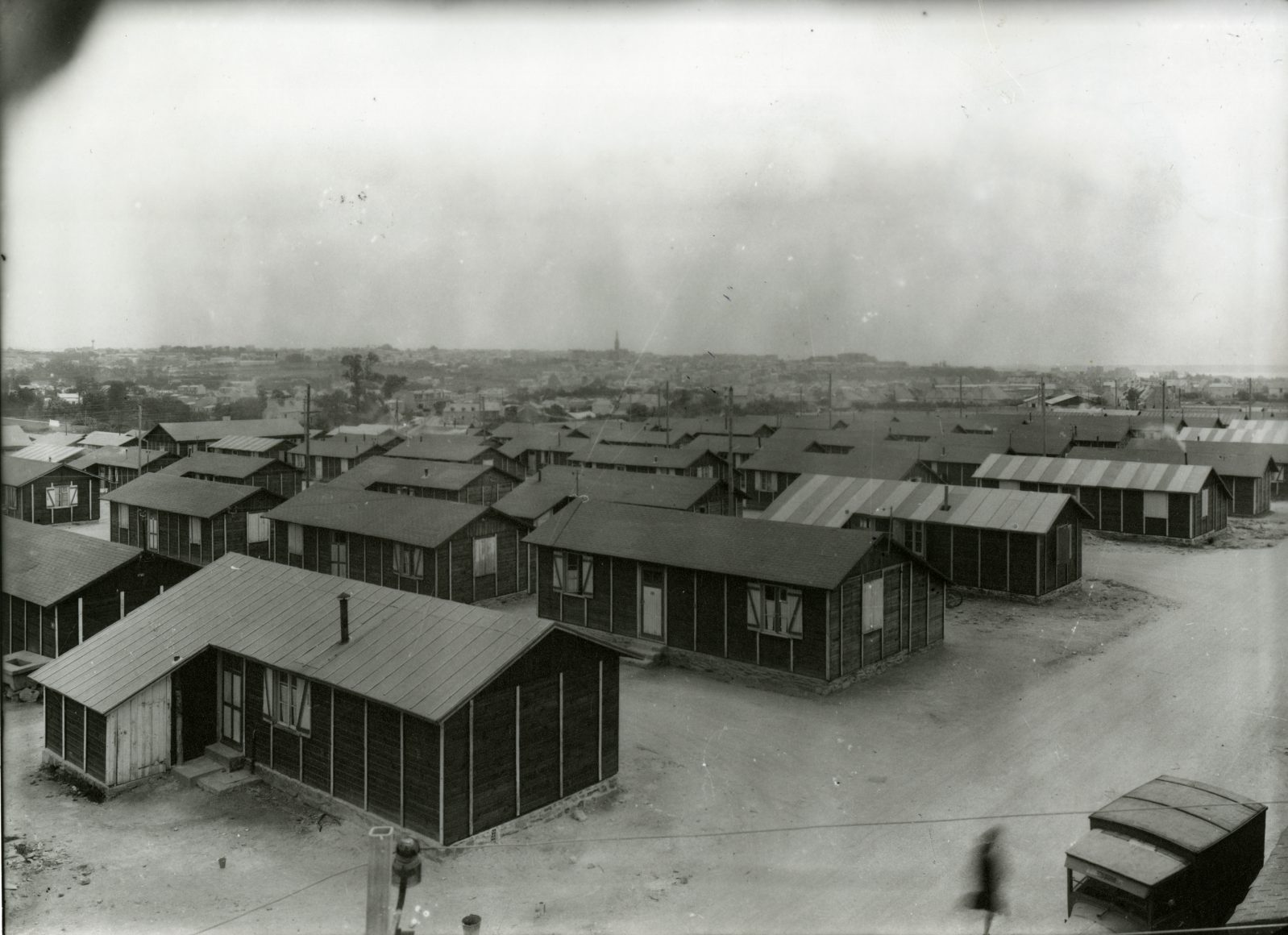

Cité commerciale dans les baraques (cote : 2Fi02823).

Baraques de Keredern, vers 1950 (cote : 2Fi02827).

Baraques du Polygone à Brest (cote : 2Fi12242).

Tours de Quéliverzan en construction, Brest, 1954 (cote : 2Fi03155).

La construction du pont de l’Harteloire, 1950, photo Studio Le Bigot – St Pierre, Brest (cote : 2Fi10236).

Association Vivre la rue :

Photographies de la rue Saint-Malo investie par l’association Vivre la rue.

Brest Métropole :

Agence ABC (Stéphane Füzesséry & Paul Landauer), Dessin du projet Grand Balcon, 2022.

Musée des Beaux-Arts Brest métropole :

Louis-Nicolas Van Blarenberghe (Lille, 1716 – Fontainebleau, 1794), Vue du port de Brest (vue prise de la terrasse des Capucins) (inv. 981.18.1), 1774, huile sur toile, 125,5 cm x 194 cm.

Claude Jean-Baptiste Jallier de Savault (?, 1738 – Paris, 1807), Projet de place Louis XVI à Brest (inv. 979.3.1), 4/4 du XVIIIème siècle, aquarelle et encre noire sur papier, 35,2 cm x 64,6 cm.

Georges Muller, d’après Alfred Guesdon (Nantes 1808 – Nantes, 1876), Brest, vue générale du Port prise de la Rade (série Voyage aérien en France) (inv. 964.5.1), vers 1850, lithographie sur papier, 40,1 cm x 56,6 cm.

Charles Villemin, d’après Alfred Guesdon (Nantes 1808 – Nantes, 1876), Brest, vue de la Ville et de la Rade prise des Glacis (série Voyage aérien en France) (inv. 960.13.25), vers 1850, lithographie aquarellée sur papier, 54,9 cm x 75,1 cm.

Autres / Collections particulières (France) :

Brest, port océanique, plan commercialisé en 1919.

Eugène Freyssinet, Pont Albert Louppe, photographie des années 1930.

Construction du pont Albert-Louppe, de la brochure Le pont Albert Louppe, Finistère, éditée par la Société anonyme des entreprises Limousin en 1930.

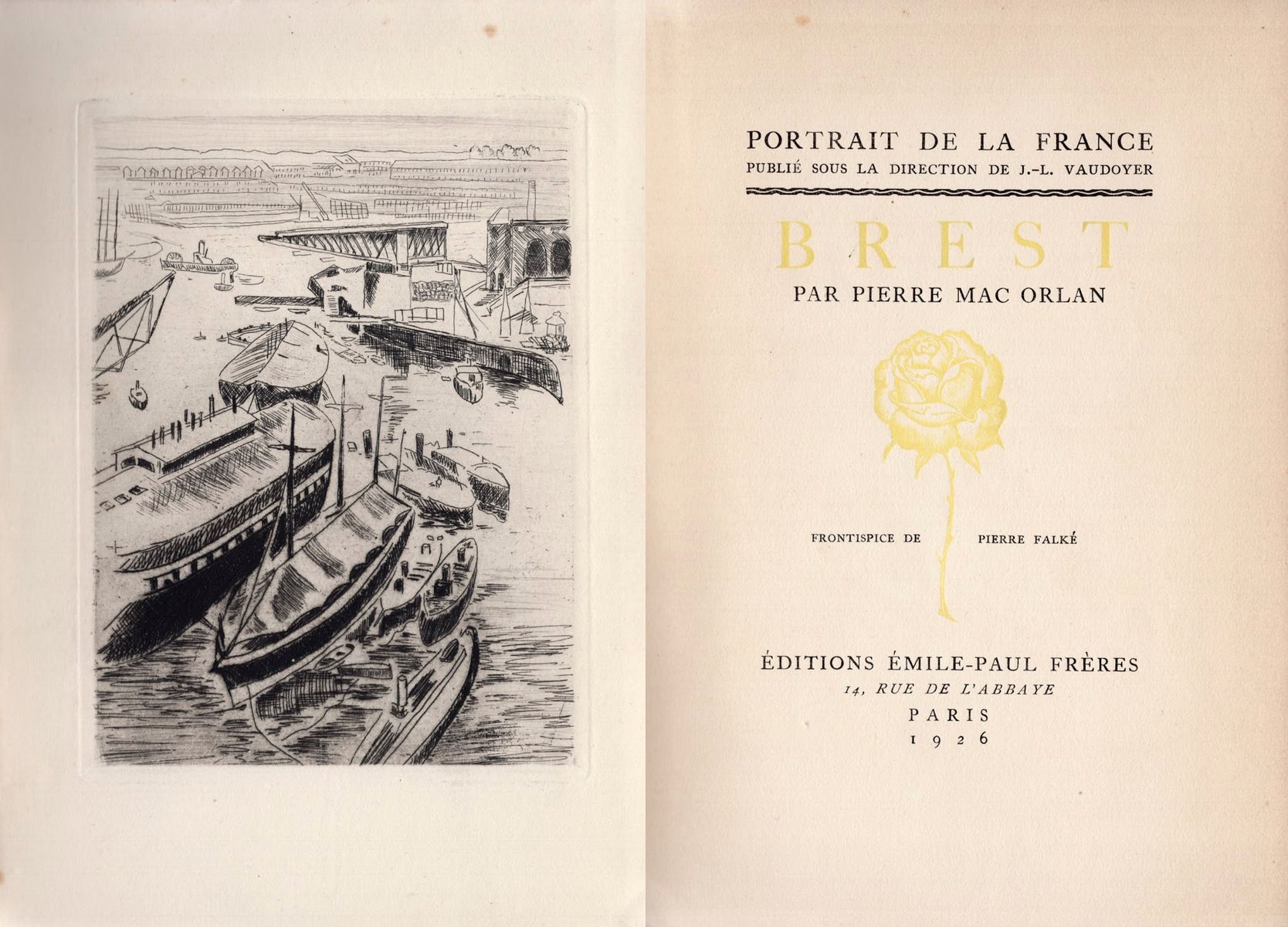

Frontispice du livre Brest écrit par Pierre Mac Orlan, gravure de Pierre Falké, 1926, Paris, éd. Emile-Paul frères.

Gare de Brest, arch. Urbain Cassan, 1937, photographie argentique.

Brest en ruines, au lendemain du siège, 1944, photographie argentique.

Brest après la guerre, photographie argentique.

Jean-Baptiste Mathon, Place de la Trésorerie, Brest, dessin aquarellé, 1948, originaux perdus.

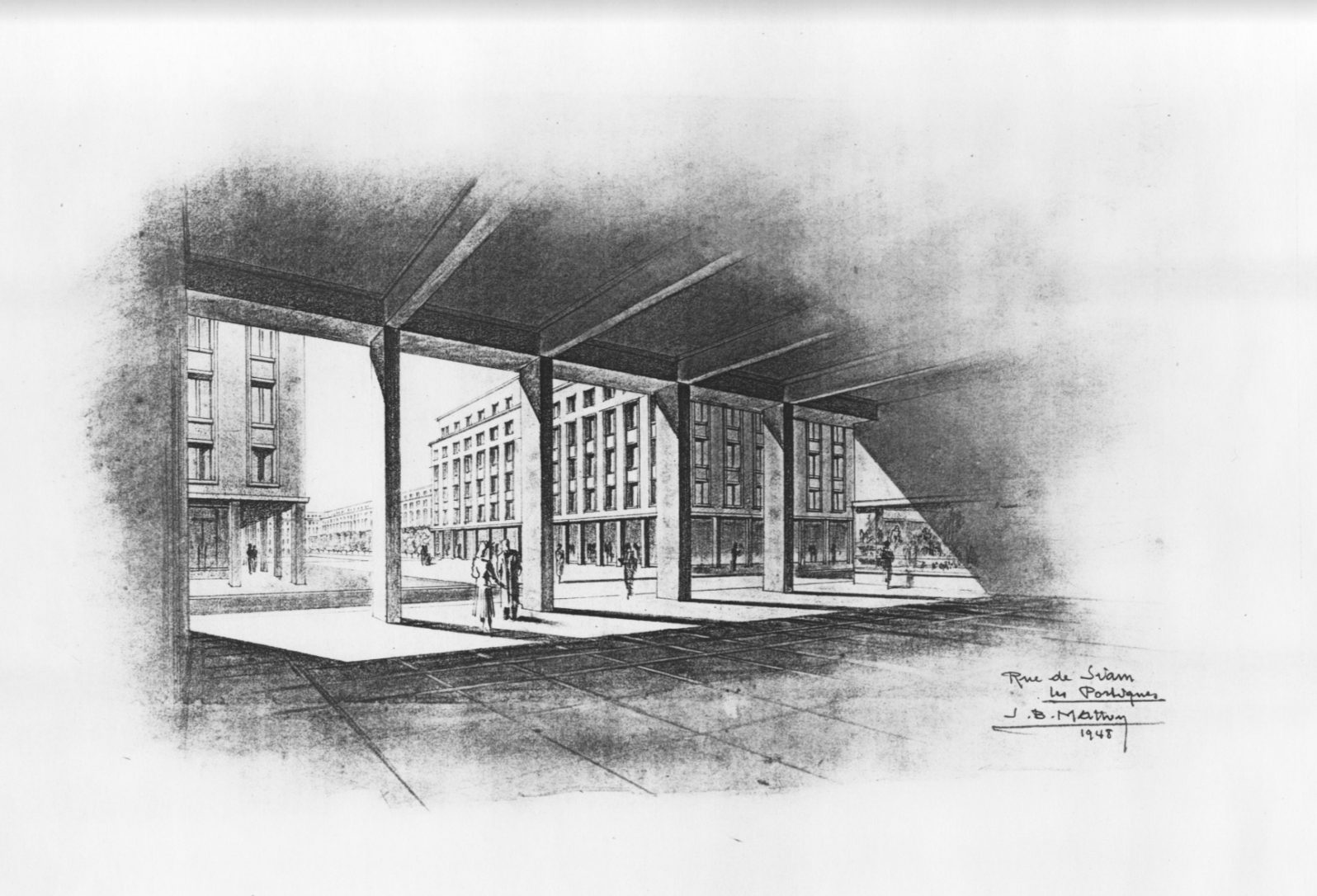

Jean-Baptiste Mathon, Rue de Siam, les Portiques, Brest, dessin aquarellé, 1948, originaux perdus.

Place de la Liberté et perspective de la rue de Siam vues de l’Hôtel de ville, années 1980, photographie argentique.

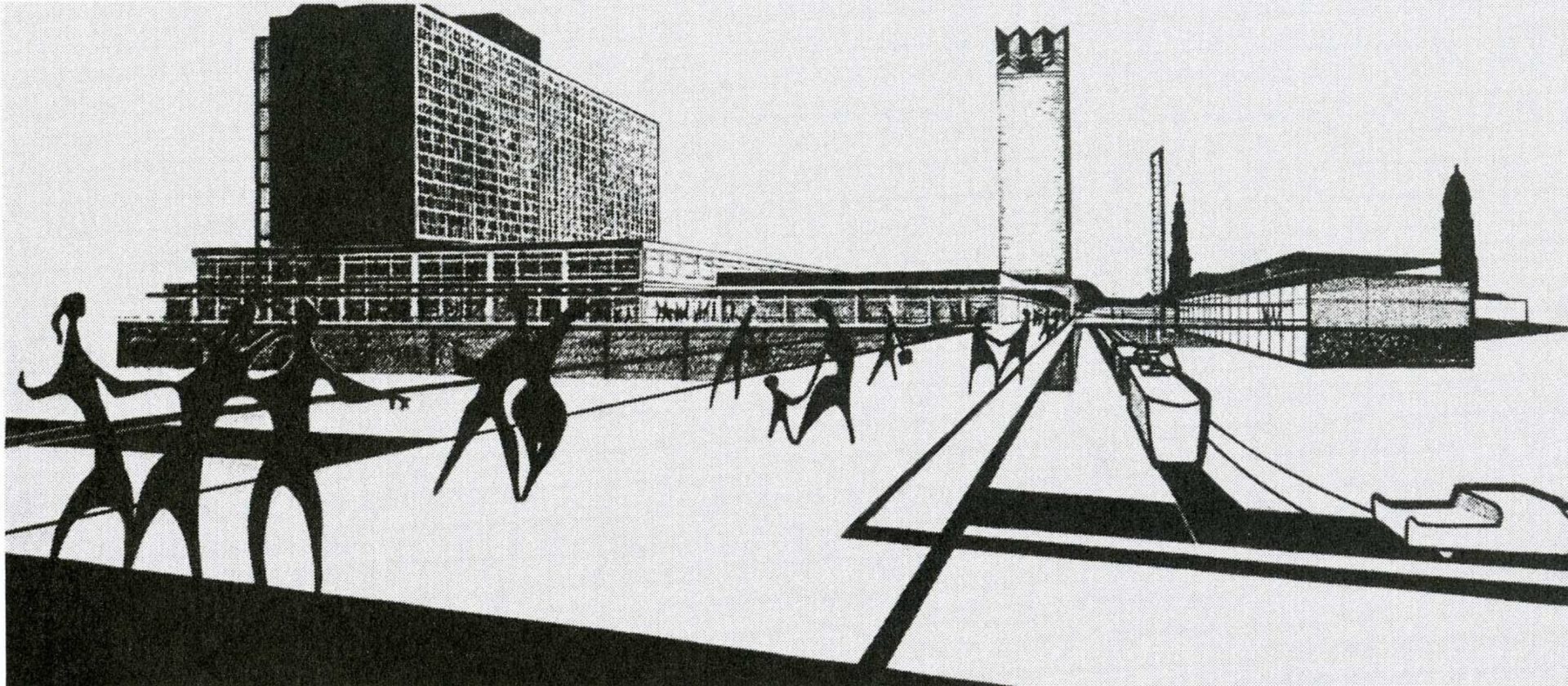

Anonyme, Proposition pour la place de la Liberté et le square Mathon, Concours d’idées, dessin, 1980, ADEUPA.

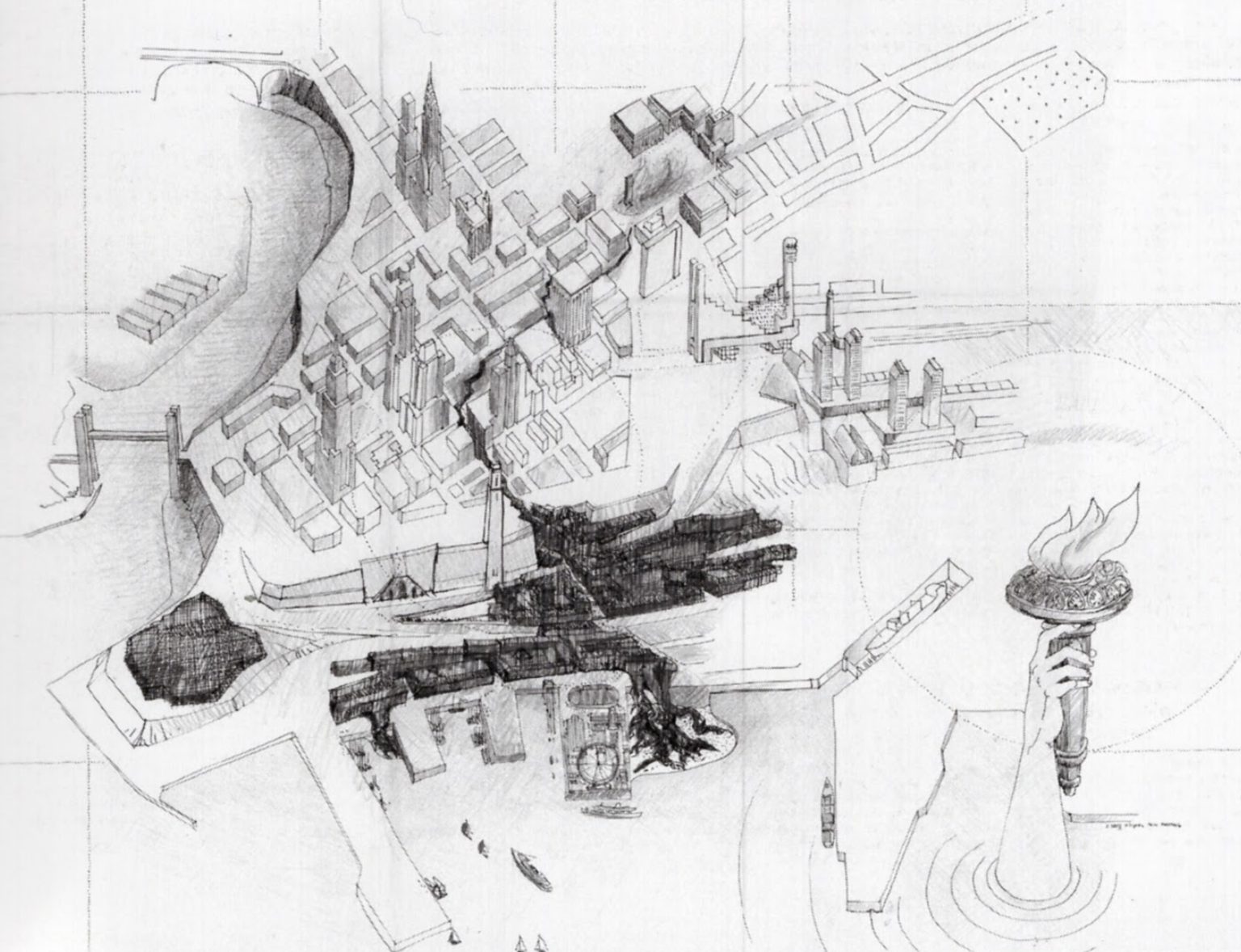

Yves Steff & Maxime Giraud-Mangin, New York’s sister, projet pour le Concours d’idées, dessin, 1980.

Renovierte Fassaden von Wohnblöcken aus der sozialistischen Ära, Dresden, Foto Quentin Arnaud, 2021.

Kunsthofpassage, Neustadt, Dresden, Arch. Heike Böttcher, 1999, photographies numériques 2022.

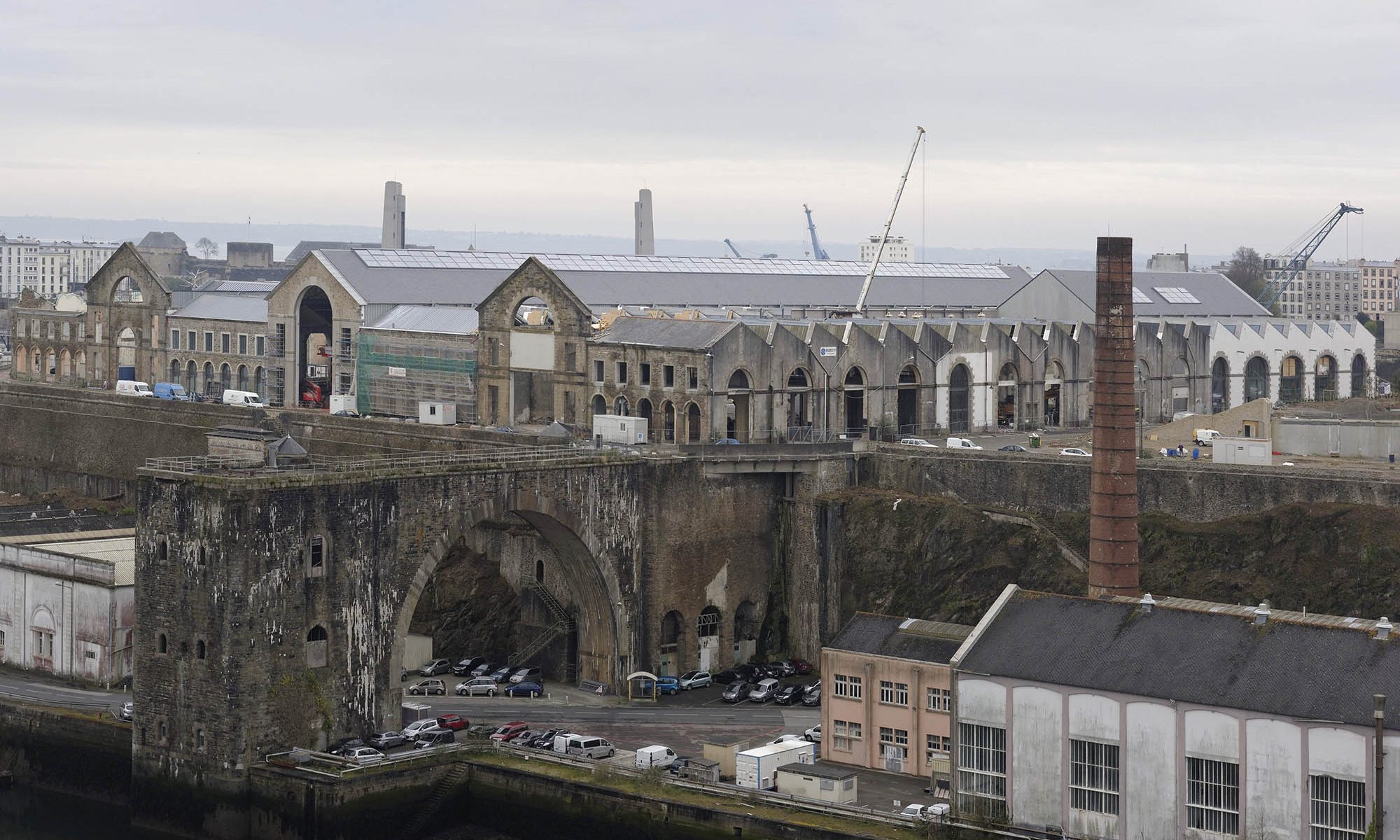

Jean-François Mollière, Le Plateau des Capucins en travaux, avril 2016.

Frédéric Le Mouillour, Brest. Quartier de Kérigonan, 2013.

Stéphane Couturier, Place Georg Treu à Dresde, photographie de la série Archéologie urbaine, 1997.

Gwenaëlle Magadur et Sylvain Le Stum, La ville en mutation, 2006-2011, Proposition d’installations sur les rives de la Penfeld, Dessins des origines du quartier de Recouvrance, rive droite et du quartier des Sept Saints, rive gauche. Dans le cadre de la résidence conjointe plasticien/architecte, soutenue par la DRAC Bretagne et la ville de Brest.

Gwenaëlle Magadur, La carte de la Ligne bleue, 2006, La carte de la Ligne Bleue, proposée en 2006 pour une forme pérenne, marque la « petite ceinture des remparts », historiquement antérieure à la grande. Rives droite et gauche de la Penfeld.

Gwenaëlle Magadur, La Ligne Bleue, Brest, 2000, Carrefour de la rue Antoine de Saint-Exupéry et Pierre Loti. Rive droite de la Penfeld. Place de la Liberté. Avenue Georges Clémenceau. Rive gauche de la Penfeld. Installation éphémère réalisée avec le soutien de la ville de Brest, du département du Finistère et de la région Bretagne, La Ligne Bleue marque la « grande ceinture des remparts ».

Wen2, Images de Brest : Le Vauban, La Recouvrance, Triskell.

Akademie der Künste Berlin:

Hans Scharoun, Entwurf zum Wettbewerb von 1920 für das Deutsche Hygiene-Museum, im Hintergrund der Zwinger, Baukunstarchiv der Akademie der Künste Berlin, Hans-Scharoun-Archiv Nr. 1228 Pl.28/11.

Architekturmuseum TU München:

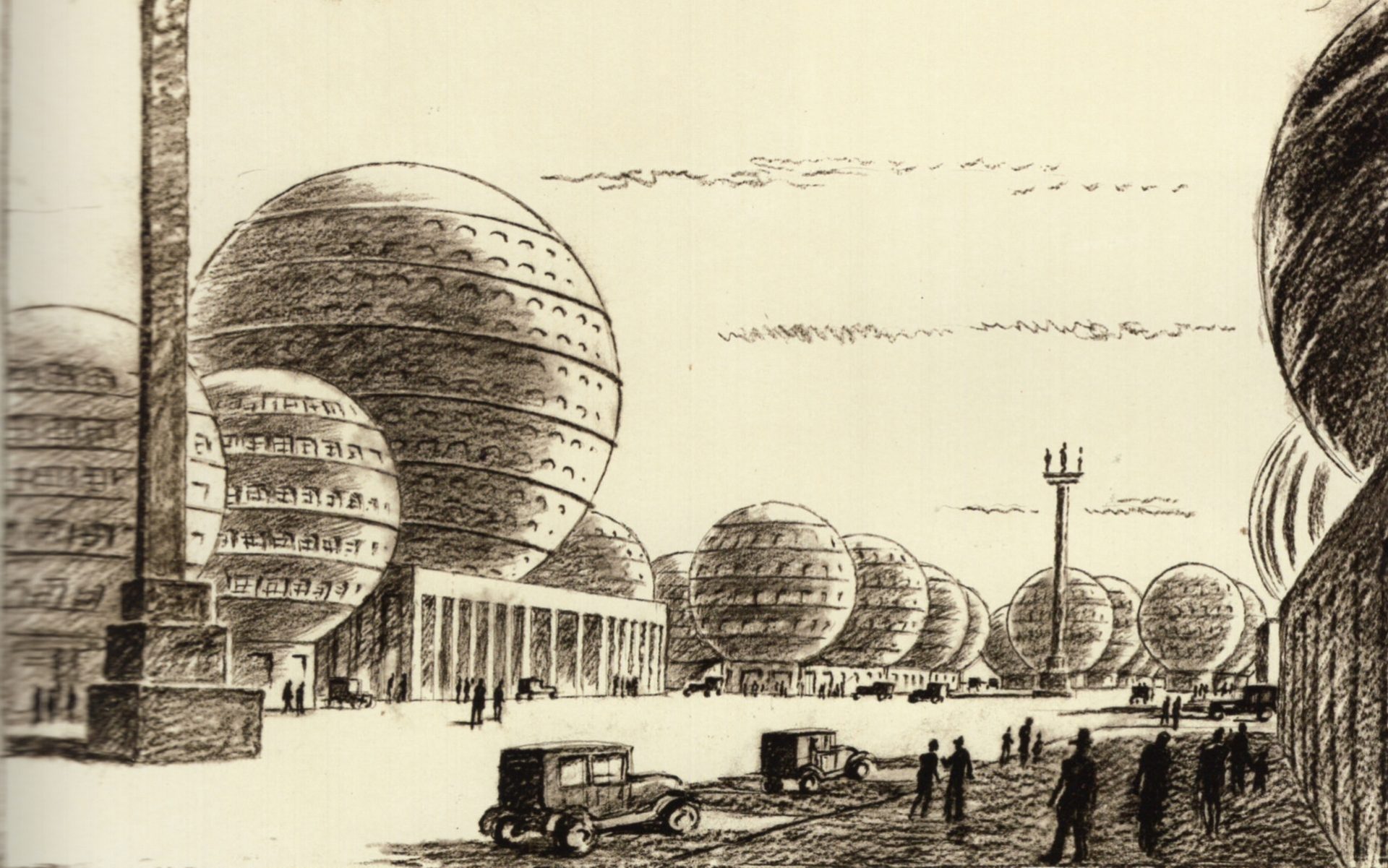

Peter Birkenholz, Zeichnung Kugelhausstadt, 1927, Architekturmuseum der TU München, Sign. bir-369-4.

Bundesarchiv Koblenz:

Ulrich Häßler, Kulturpalast Dresden (Arch. Leopold Weil & Klaus Wever, 1966-69), 1985, Bild_183-1985-0918-026.

Cinémathèque de Bretagne

Ce Brest dont il ne restait rien, Jean Le Goualch, 1944 à 1964, 16mm, noir et blanc, sonore, n°4597 : https://www.cinematheque-bretagne.bzh/base-documentaire-ce-brest-dont-il-ne-restait-rien-426-4597-0-1.html?ref=7538b411cc12adf993b5b55c8a450853.

Archives américaines 4 / 208-UN-1041, National Archives and Record Administration (at College Park) ,1942 à 1945, noir et blanc, sonore, n°25720 : https://www.cinematheque-bretagne.bzh/base-documentaire-archives-américaines-4-426-25720-0-1.html?ref=eb1dcbdc0efa0f8dd11cffb4a0e6adfb.

Gemäldegalerie Alter Meister Dresden:

Bernardo Bellotto, genannt Canaletto oder Canaletto der Jüngere, Dresden vom rechten Ufer der Elbe aus gesehen, unterhalb der Augustusbrücke, 1747, Öl auf Leinwand.

Bernardo Bellotto, genannt Canaletto oder Canaletto der Jüngere, Ansicht von Dresden. Der Neumarkt in Dresden vor Jüdenhofe, mit Frauenkirche im Hintergrund, 1748, Öl auf Leinwand.

Hygiene-Museum Dresden:

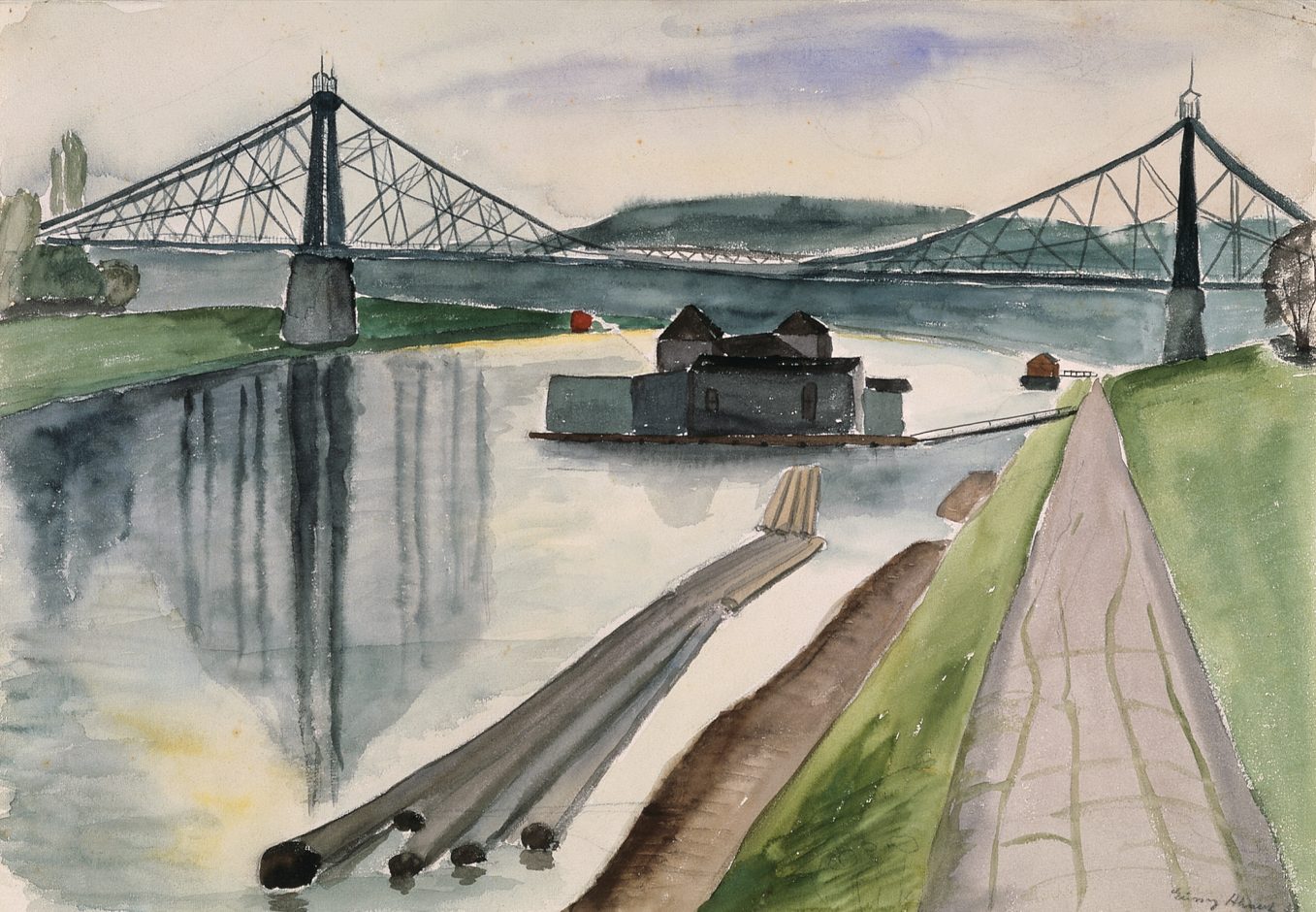

Gussy Hippold-Ahnert, Badeanstalt am Blauen Wunder, 1935, Aquarell, DHMD 1995/56.

Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Sachsen:

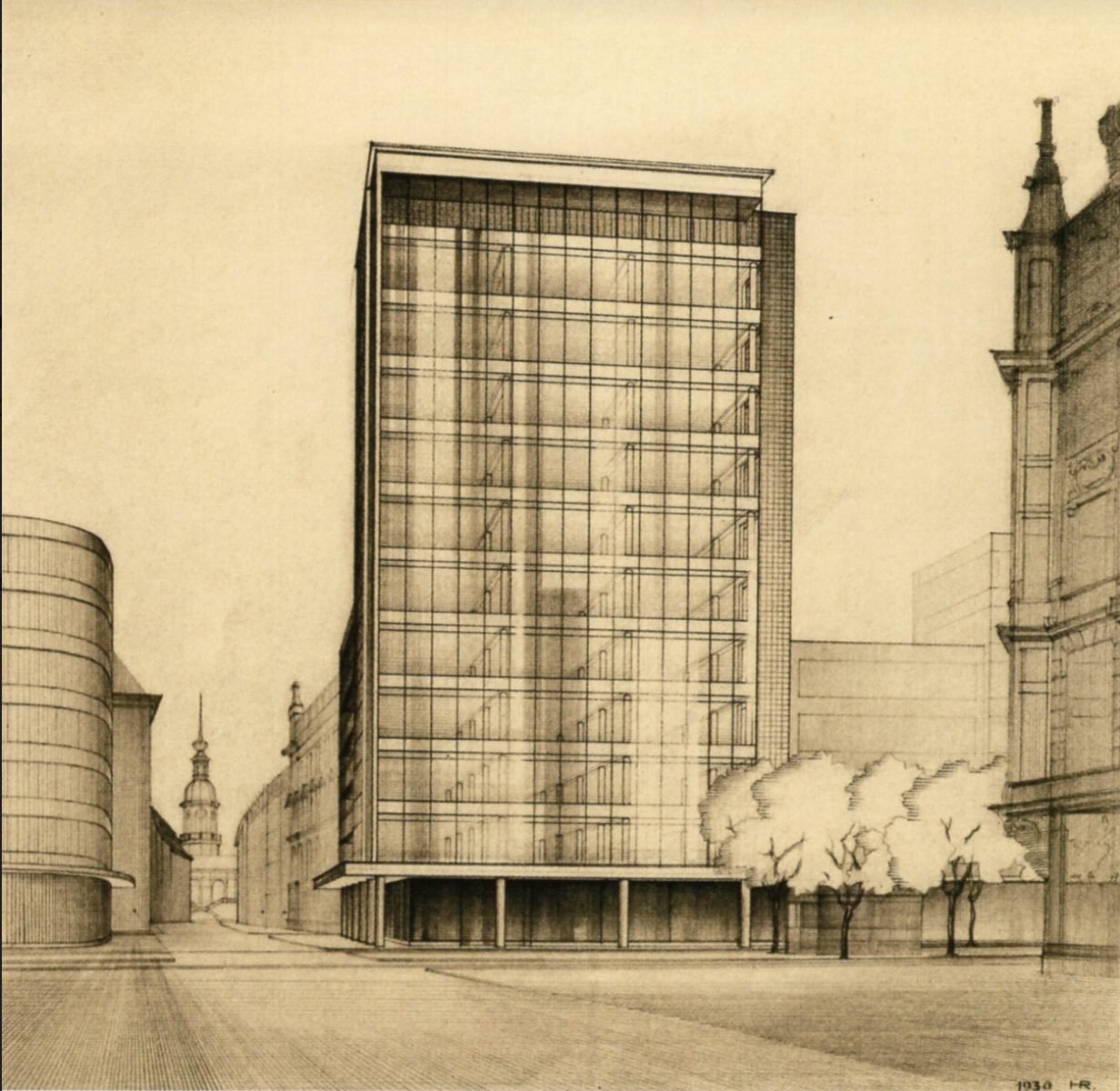

Hans Richter (14.04.1882 Königswalde/Böhmen – 10.12.1971 Dresden), Dresden, Hochhaus am Pirnaischen Platz, Ansicht von Osten mit Umgebung (angeschnitten), um 1930, bezeichnet in der Darstellung u. r. mit Bleistift „1930 HR.“ (ligiert), auf dem Blatt u. l. auf aufgeklebtem Papier maschinenschriftlich „hochhaus pirnaischer platz // blick von der grunaer straße“, Bleistift auf Zeichenkarton, Blatt 69,8/70,0 cm x 49,4/49,7 cm (unregelmäßig), LfD Sachsen, Plansammlung, Inv.-Nr. 2019/1.

SLUB Dresden Deutsche Fotothek:

Hahn, Walter: Dresden. Hauptbahnhof. Gleisanlagen, Empfangsgebäude., Bahnsteighalle. Luftbild-Schrägaufnahme von Südosten, 1925.05, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0304975, Negativ (Glas, 4 x 5 inch, schwarzweiß).

Hahn, Walter: Dresden-Striesen. Stadtteilansicht mit Waldersee-Platz (Stresemannplatz). Luftbild-Schrägaufnahme von Osten, 1924, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0305774, Originalnegativ (Glas, 10 x 15 cm, schwarzweiß).

Hahn, Walter: Dresden. Blick vom Rathausturm mit Skulptur auf die zerstörte Innenstadt, 1945, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0314636, Negativ (Glas, 13 x 18 cm, schwarzweiß).

Hahn, Walter: Südvorstadt mit Landgericht, Blick nach Nordosten, 1932, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0310213, Originalnegativ (Glas, 13 x 18 cm, schwarzweiß).

Peter, Richard sen.: Dresden nach der Bombardierung vom 13./14. Februar 1945, nach 1945.09.17, Aufn.-Nr.: df_ps_0000364_001, Originalnegativ (Kunststoff (Zellulosenitrat), 24/36 mm, schwarzweiß).

Peter, Richard sen.: Dresden. Zerstörtes Lutherdenkmal vor der Ruine der Frauenkirche, nach 1945.09.17, Aufn.-Nr.: df_ps_0000385_001, Originalnegativ (Kunststoff (Zellulosenitrat), 3/4 cm, schwarzweiß).

Peter, Richard sen.: Pragerstraße, Pusteblumenbrunnen / Am Pusteblumen Brunnen, 1968, Pragerstr., Aufn.-Nr.: df_ps_0002955, Originalnegativ (Kunststoff, 6/9 cm, schwarzweiß).

Peter, Richard sen.: Wasserspiel mit Schalen, um 1975, Aufn.-Nr.: df_ps_0001024, Originalnegativ (Kunststoff, 6/6 cm, schwarzweiß).

Peter, Richard sen.: Blick zum Interhotel “Newa” (links; 1968-1970; C. Kaiser, M. Arlt, H. Fuhrmann, J. Weinert) und zu Appartementhochhäusern (1965-1966; J. Kaiser, P. Schramm), 1973, Aufn.-Nr.: df_ps_0001006, Originalnegativ (Kunststoff, 6 x 6 cm, schwarzweiß).

Bauwerk: Frauenkirche, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0138038, Negativ (schwarzweiß).

Möbius, Walter: Ruine der Frauenkirche mit weidenden Schafen, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0135395, Reproduktionsnegativ (Kunststoff, 13 x 18 cm, schwarzweiß).

Bauwerk: Hotel Newa, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0188254, Originalnegativ (Kunststoff, 13 x 18 cm, schwarzweiß).

Johann Christoph Knöffel, Frauenkirche, Schnitt, ohne Datum (1720er Jahre), Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Sachsen, Repro Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0050880, Negativ (schwarzweiß).

Meser, C.F.: Blick von der Brühlschen Terrasse auf die Hofkirche, Radierung, um 1825, Aufn.-Nr.: df_dk_0013303, Datensatz (color).

François de Cuvilliés der Ältere: Fiktive Planzeichnung zur Neubebauung Königlichen Residenz, Projekt zur Entfestigung von Dresden, Handzeichnung, um 1761, 2020, Aufn.-Nr.: df_dk_0013309, Datensatz (color), SächsHStA, 12884, Karten und Risse, F 145; Nr. 12a.

Pöppelmann, Dresden. Zwinger. Entwurf Torturm, 2006, Aufn.-Nr.: df_dz_0000001

Datensatz(color).

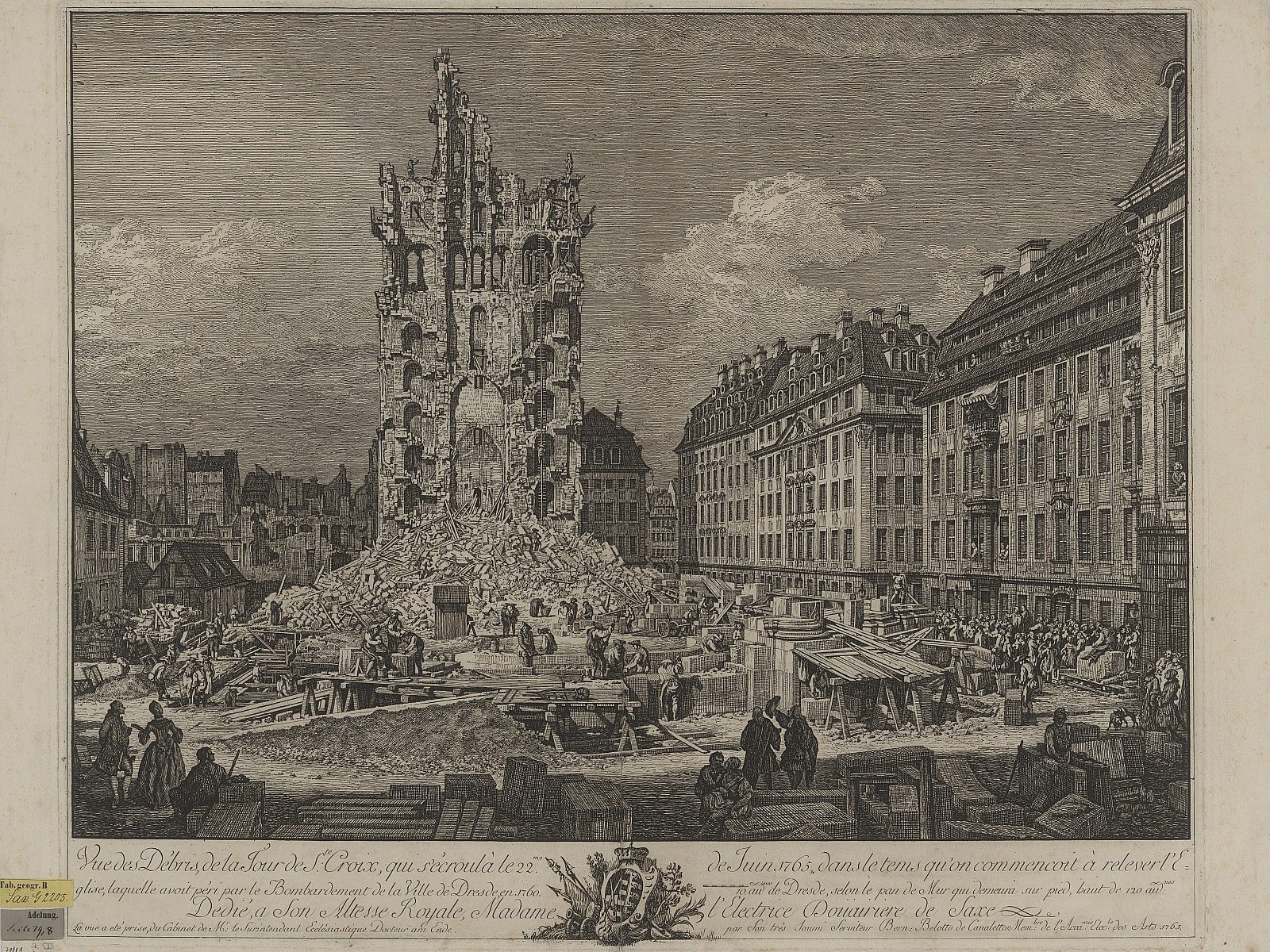

Bernardo Bellotto, genannt Canaletto oder Canaletto der Jüngere, Ansicht der eingestürzten Kreuzkirche in Dresden, 1765, Kupferstich ; 63 x 47 cm, Aufn.-Nr.: df_dk_0003827, Datensatz (color).

Bässler, Wilhelm: Ansicht vom Bau der Marienbrücke, Lithographie, 1849, Aufn.-Nr.: df_dk_0008829, Datensatz (color).

Reinecke, Hans: Panorama der Augustusbrücke und des Neustädter Ufers in Dresden, 1991, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0266677, Originalnegativ (Kunststoff, 13/18 cm, schwarzweiß).

Möbius, Walter: Dresden-Altstadt, Almarkt. Blick vom ehem. Modehaus Möbius über Baustelleneinrichtungen gegen Wohn- und Geschäftshäuser, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0127231, Originalnegativ (Glas, 13/18 cm, schwarzweiß).

Nagel, Heinz: Dresden, Ansicht vom Dach des Ständehauses über den Altmarkt nach Südsüdwest, 1957.05, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0134776, Originalnegativ (Glas, 13 x 18 cm, schwarzweiß).

Döring, Gerhard: Blick vom Schloßturm über die Ernst-Thälmann-Straße (Wilsdruffer Straße) zum Altmarkt, Rathausturm und Kreuzkirche nach Südosten, 1965.08, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hauptkatalog_0163062, Originalnegativ (Glas, 13 x 18 cm, schwarzweiß).

Höhne, Erich & Pohl, Erich: Dresden, Altmarkt, Neubebauung, Oktober 1954, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hp_0005554_017, Negativ.

Höhne, Erich & Pohl, Erich: Dresden, Altmarkt. Neubebauung, Walter Weidauer auf der Baustelle – Blick zur Ruine der Sophienkirche, September 1953, Aufn.-Nr.: df_hp_0005652_001, Negativ.

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden:

Wilhelm Rudolph, Frauenkirche in Dresden, o.J., Lithografie 37,8 x 39,9 cm, Kunstfonds, © SKD, Foto: Sabine Ulbrich.

Wilhelm Rudolph, Zöllner Straße, undatiert (nach 1945), Holzschnitt, Handruck, 53,5 x 76,2 cm, Kunstfonds © SKD, Foto: Stefanie Recsko.

Georg Christian Fritzsche Aufzug der Wagen und Reiter zum Damenfest am 6. Juni 1709, Amphitheater von M. D. Pöppelmann und Johann Friedrich Karcher, Kupferstichkabinett.

Stadtarchiv Dresden:

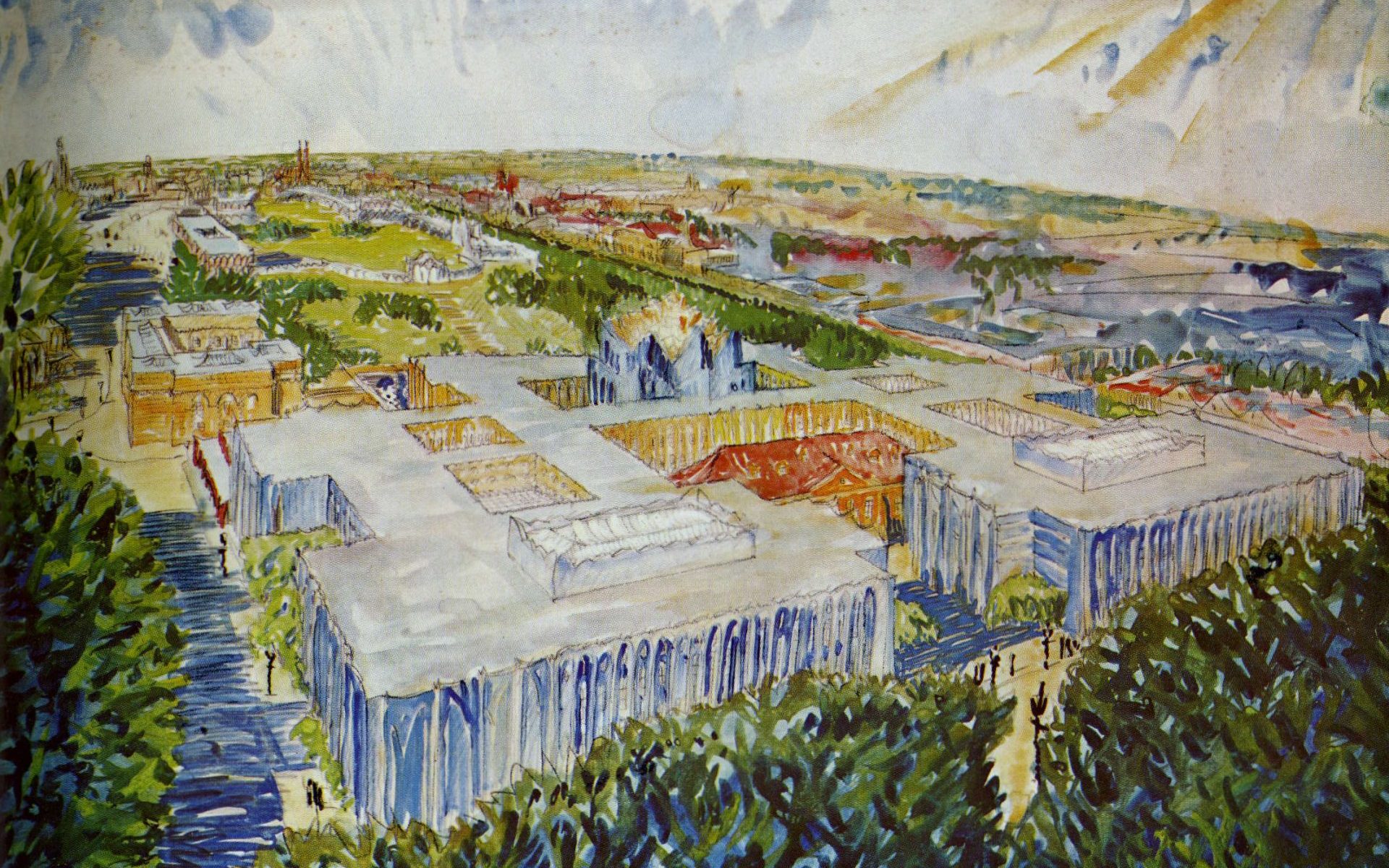

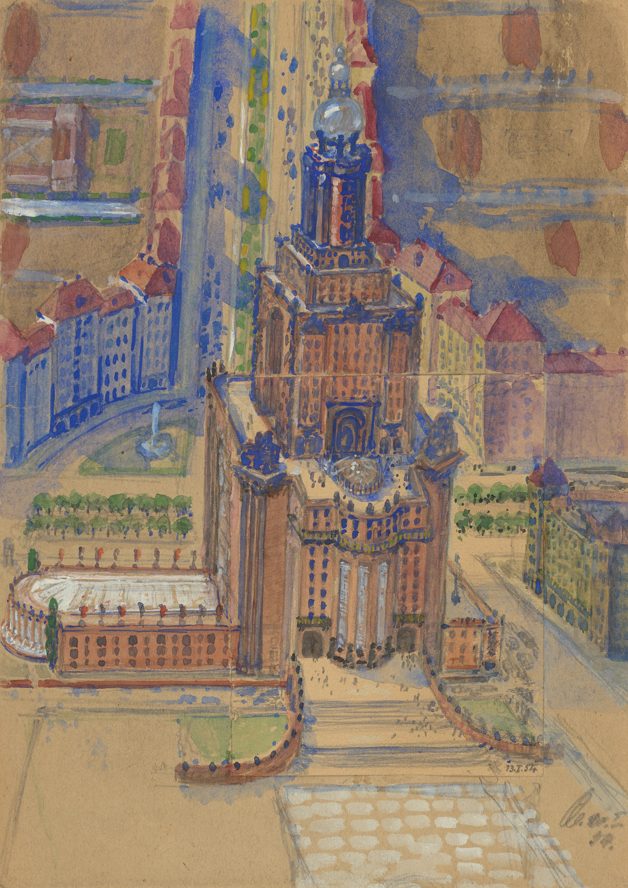

Herbert Schneider, Vorschlag für den Wiederaufbau von Dresden, 1946, Stadtarchiv Dresden, 6.4.40.1 Stadtplanungsamt Bildstelle, Nr. XIII5156, Fotograf/in unbekannt.

Fritz Müller, Neues Dresden, Entwurf 1946, Landeshauptstadt Dresden, Stadtplanungsamt, Schlüssel XIII5070.

Hanns Hopp, Neues Dresden, 1946, Perspektive der Stadtmitte vom Hauptbahnhof zum Altmarkt (G. Wiesemann in ihrer Monographie zu Hanns Hopp [2000]”).

Mart Stam, Aufbauplan, 1946, Landeshauptstadt Dresden, Stadtplanungsamt, Schlüssel XIII4018.

Prager Straße vom Newa ausgesehen, 1970, 6.4.40.1 Stadtplanungsamt Bildstelle, Nr. I6869, Fotograf·in unbekannt.

Stadtmuseum Dresden:

Oswald Enterlein, Entwurf für ein Kulturhaus am Altmarkt, 1954, SMD/SD/2021/00203.

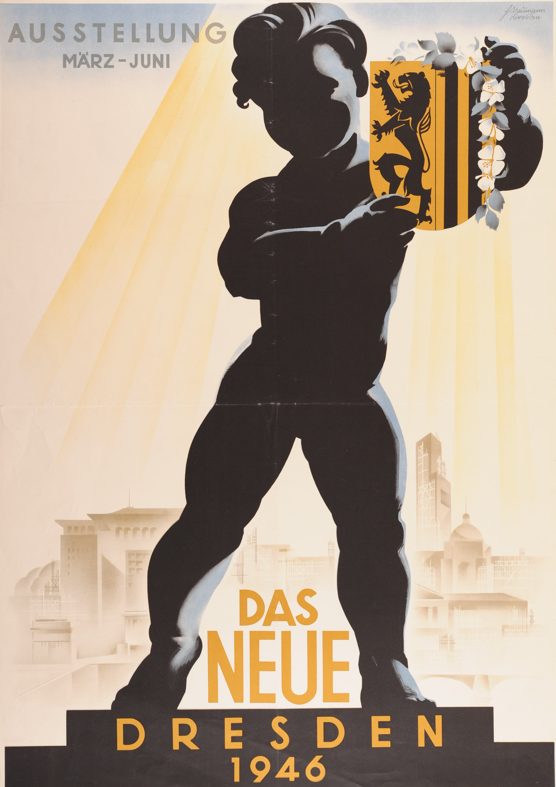

Horst Naumann, Plakat Das neue Dresden. Ausstellung vom Marz – Juni 1946 in der Stadthalle am Nordplatz, SMD/SP/1985/01050.

Andere / Privatsammlungen (Deutschland):

Klaus Willem Sitzmann, Photographie Frauenkirche & Neumarkt.

Birgit Schuh, Schokofluss, Dresden, 2011.

Kirsten Kaiser, Mnemosyne, Wasserkunstwerk der Dresdner Sezession 89 e.V., Dresden, 1993-2000.

Kraftwerk Dresden Mitte, Fotograf: Oliver Killig¨.

Nils Schinker, Stadtentwicklung Dresdens 1919 bis 1933 (in Rot die neuen Gebäude aus den 1920er und 1930er Jahren.

Wikipedia:

Dresden-Äußere Neustadt, Böhmische Straße, August 1993.

Bunte Republik Neustadt Dresden.

Universitè de Bretagne Occidentale

Ivana Radovanovic, Converging Visions, 2023.